I was twenty five and restless when, after two years of boredom and frustration working for Hamilton Standard in Connecticut, I was mercifully laid off in August of 1969. The lay-off occurred while I was on a two-week vacation that I had spent driving out to Utah and back. It was during that trip that I met the relatives of one my co-workers in Logan, Utah . As it turned out, it was these gracious people with whom I would later board. The night I arrived back in Connecticut, I was notified that I didn’t have a job.

I was disillusioned with being a mechanical engineer if all I had to look forward to was a career of wasting the government’s defense contract money on make work projects, while working for defense contractors. I was considering changing to a career of real work by enrolling in a school with an Airframe and Powerplant Mechanic’s course, preferably out West where the scenery is different. After a couple weeks of lying in the sun, I decided that was what I would do. I enrolled in the Aeronautical Technical course at Utah State University in Logan, and headed west with all my earthly possessions, a new ’69 Toyota, a beat up ’59 VW micro bus and a 1946 Taylorcraft. I wasn’t ever coming back. I had purchased the bus from another EAA member earlier that summer, and upon hearing of my plans, he assured me that the mighty 36 horse engine would never pull the bus out to Utah, let alone with a Toyota hitched to the back. But that’s what I did.

Progress across the country was excruciatingly slow. At no time was I capable of exceeding 45 mph. Nebraska proved to be formidable. The combination of the long upgrade westward and a steady headwind was deadly. Progress was much enhanced after I chanced to pick up a college student along the interstate in Nebraska. He was hitchhiking to Utah and I turned him loose in the micro bus while I followed in the Toyota.

After arriving in Logan and making living arrangements, the micro bus was given a well-earned rest, and the Toyota was used to drive back down to Salt Lake City to catch a commercial flight back to Connecticut to retrieve the Taylorcraft. So there I was, trudging through the terminal lobby with a suitcase and a misshapen roll of a sleeping bag with all my cooking utensils rolled up inside, and I ran smack into a dorm mate from my University of Massachusetts days. He had gone through ROTC and was now stationed out at Hill AFB in Ogden. He just happened to be at the airport, seeing a girl friend off for Europe. After a quick update of my latest adventures, he saw me off, too, on the next flight. He left shaking his head. He also left with my car, which he parked back at the Air Base, thus saving me a healthy parking fee.

I arrived back in Connecticut relieved that the Coleman stove rolled up in my sleeping bag didn’t blow up in the baggage hold of the airliner. A couple of nights were spent sleeping on the hanger floor at Simsbury Airport while waiting for a stretch of good weather to come along. Then it was off west again, in the Taylorcraft, outfitted with sleeping bag, one-burner stove, a jug of water, tea bags, a loaf of bread, a jar of peanut butter, and a handful of WAC charts. The sky was CAVU. Navigation was made easy by following Interstate 90 across New York state after a 7am departure. The first day’s travel with gas stops in Seneca Falls, NY, Ashtabula, Ohio and Valparaiso, Indiana took me clear beyond Chicago, where just as the sun settled onto the horizon, I settled onto a grass strip at Ottawa on the Illinois River. That was about 1100 miles in one day of travel. An unusual westerly tailwind helped. It was 7 pm, and the airport attendant was gone. I tied down and made myself at home under the wing. The seat and back cushions laid end-to-end on the ground made a perfect mattress.

Before I could get off the next morning without paying, the attendant showed up, but I guess the hand prop was worth the price of the tie down. The attendant watched wistfully as I taxied out and took off. I crossed the Mississippi at Davenport, then got gas at Perry, northwest of Des Moines and again at Fremont, northwest of Omaha. The air got quite turbulent over Nebraska as the sun warmed up the ground. It was hard holding an intelligible conversation with the control tower with my head beating against the side of the cockpit, but I managed to get into North Platte, Nebraska that afternoon before sunset. Now let me tell you about North Platte.

I walked up to the counter in the FBO’s lounge and asked if I could sleep under my plane, a simple enough request, I thought. Well, “No sir, this a municipal airport with a chain link fence all around, and it’s patrolled by a night watchman, and, no, you may not sleep in, under, nor on top of your plane, nor anywhere on the airport property, for that matter.” I got the distinct impression that I wasn’t welcome, so with bedroll in hand, I proceeded out the airport drive and a half mile down the road where I found a secluded place down an embankment behind a closed-up weigh station. By now it is pitch black. No sooner had my sleeping bag hit the ground when a police cruiser pulled up and put its megawatt spot light on me. They must have had me on radar. It was obvious to them that I was a fugitive from somewhere. They weren’t buying the story that I was a pilot and had flown in, especially since I’d left my wallet back in the plane. So it was into the cruiser and back to the airport to show them the plane and my pilot’s license. They bought the story now, but couldn’t understand why a rich airplane driver didn’t stay in a motel. Explaining that I was just a poor college student on my way to school and that the price of a motel room would finance a full day of flying, only brought the suggestion that I sleep on a park bench in town three miles down the road. They didn’t offer to take me there, though. So it was “back to square one”, down the airport drive, bedroll in hand, and down the road again, past the weigh station to town. Patience shall triumph. Just a quarter mile out of town, another police cruiser pulled up beside me. I was ready to pound sand, but the officer just leaned out the window and asked, “Say, are you the one…”. I cut him off in mid-sentence, “Yep, I’m the one.” Imagine, only two hours in town and already I was a legend. They told me to hop in back; they’d give me a lift the rest of the way. The accommodations on the park bench were just fine, the mercury vapor lamp overhead notwithstanding, and there were no further incidents. I resolved to come back some day with a renegade squadron and bomb the town to rubble.

The next day’s journey was a high. After fueling at Scottsbluff, I left the highways and civilization behind and headed due west for the Medicine Bow Vortac, skimming across the 7,000-foot high prairie of Wyoming, chasing herds of wild horses and antelope, strafing Union Pacific freight trains and rocketing over the edge of bluffs. I pulled into 6784 foot high Rawlins that afternoon just ahead of an approaching squall line from the west. Since there were no tie downs left, the FBO at the little strip insisted that I put my plane in his hanger. When I asked if I could sleep in his hanger with my plane, he didn’t even flinch. He even told me to help myself to his old Econoline if I wanted to go into town, which I did. I had my first hot meal; a pair of hot dogs. The next morning he told me to help myself to coffee in his office, then wouldn’t even take a tie down fee for my plane. If North Platte was ‘yin’, then Rawlins was ‘yang’. I must return someday and refuel my renegade squadron here, on my bombing mission to North Platte.

The fourth day out was just a short hop across the Wasatch Mountains. Being cautious, I climbed to 11,000 feet well ahead of the mountains. While up there a camouflaged B-52 passed well below me headed in the opposite direction. At first I thought the ground was moving by awfully fast. The Wasatch range in this vicinity tops out at 9980 feet above sea level, so this was one of the highest mountain crossings I would ever make. Noontime found me coasting down into the Cache Valley and Logan at 4453 feet above sea level. I arrived in plenty of time for the first day of classes – just your typical college freshman student.

My time in Logan attending Utah State University included some of the best days of my life. I was boarding with a retired school teacher and her husband on a small farm out on the north end of town. I helped to earn my keep by picking apples in their orchard. To hike in the Wasatch Mountains only required going out the back door and going straight up. There was a cave to explore up in Logan Canyon. And there was much to see within easy flying distance.

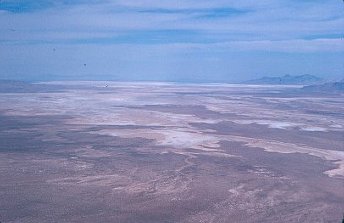

In late September, I flew to the far west side of the Bonneville Salt Flats and landed on the drag strip. Normally the salt crust is crinkled up, but on the track it had been rolled down flat and had a black stripe painted on. On the return I flew over Skull Valley to get gas at Tooele, flew down inside the Bingham open pit copper mine just to the east, and then flew over the center of Great Salt Lake.

In late October I made another cross country direct to Vernal, Utah on the edge of Dinosaur National Monument. This entailed crossing the 13,498 foot Uinta Mountains. This mountain range is remarkable in that it is the only mountain range in the country that runs east to west, and the peaks are composed of horizontal sedimentary layers. At this time I didn’t have a mixture control in my carburetor, my engine sputtered and wheezed from the overly rich mixture, and the best I could do was around 12000 feet. I had to fly between the peaks to get over. After refueling at Vernal, I headed into Dinosaur, where the Yampa River from Colorado joins the Green River from Wyoming in a maze of canyons, and the Green River then flows through the middle of a mountain. I flew down between the Yampa River canyon walls and enjoyed exploring the tortured geology.

Unfortunately I got caught up in the rapture of the wild blue yonder. I should have gone back to Vernal and topped off, because as I was crossing the Wasatch Mountains on my return to Logan, the float wire in my nose tank stopped bobbing. I didn’t know if I had one minute or five left before fuel exhaustion. I reduced power and traded altitude for distance, as I descended into Logan Canyon, staying over the winding two-lane road below. I felt like I’d been given another chance to live when I broke out into the Cache Valley. I made straight for the Logan Airport. Just as I passed over the end of the runway on crosswind, the engine quit. I glided downwind, turned base barely over the power lines, landed perpendicular to the runway on the runup ramp, then rolled out on the runway. An alert line boy saw me and raced out to meet me with the fuel truck.

The next month I did a test flight to see how high I could get, and managed to get up to 14,800 feet. The following April a mechanic gave me the mixture control parts for my carburetor, and after putting them in, I was able to get up to 18,000 feet before my freezing feet forced me to quit.

In early February I headed north into Idaho to see the Snake River canyon and the Craters of the Moon National Monument, landing at Arco, then turning east towards the Grand Tetons and landing at McCarley on the Snake River before returning to Logan. Later that month, classmate Mark Wolf and I flew out to a deserted mining strip on the end of Promontory Point, and chased jack rabbits through the sage brush. On another occasion I flew another classmate out to a family farm at Locomotive Springs, landing on a furrowed field. Life was good.

The shop classes at USU were fun without the boredom of classroom lectures. I was paired up in shop with another easterner, Charlie Souliere, from Hampton, NH, partly because of where we were from, but mostly because I was the only one who could keep him barely under control. He would flit all around the shop, bouncing from one project to another, and he could talk at mind numbing length. But he had a heart of gold, and we would become best friends, sharing many adventures in the following years.