In the spring of 1970, I emerged from Utah State University with a fresh Airframe and Powerplant Mechanic’s License after nine months of study. This was possible because my BSME degree satisfied all the classroom requirements, and I only had to take the shop courses. My next great ambition was to fly to Alaska in my own airplane. Since everyone up there flew, there was a good chance I could put my new license to use, especially with extra air activity supporting the North Slope oil boom. Who knows, I might even be able to cash in on my experience as a project engineer on C-130 propeller systems, since all the operators up there were buying C-130’s to haul freight to the North Slope.

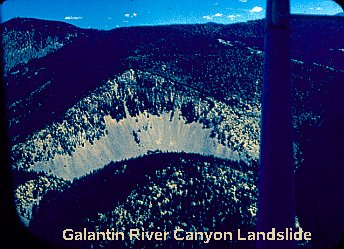

Departure took place on June 21, 1970. Armed with some US and Canadian WAC charts, Canadian ARC charts, a USAF ONC chart and an indispensable Chevron road map covering the Yukon, I set out in company with a Cessna 140 piloted by Paul Halverson, another fresh graduate. We headed due north into Idaho, then followed the Snake River upstream into Jackson Hole. After a quick pass over Yellowstone, we landed at West Yellowstone, elevation 6644 feet, for fuel. Since I planned to stay up in Alaska for awhile, I was well loaded down, and it was getting towards midday and hot, so my climb performance after taking off wasn’t too spectacular. In fact, I dragged the treetops for several miles as I struggled for enough altitude to clear the 7500 foot pass to the north into the Galantin River Canyon. Paul, in the 140, had no such problem. The Galantin River was beautiful, with rapids cutting through tall timber…and no place to land.

We attained the upper Missouri, bypassed Helena, and landed out in Montana farm country at Valier airport, where we spent the night.

The next morning we cleared customs at a small dirt strip which was conveniently located right next to the highway customs station at Ross. After a gas stop at Calgary, we battled strong headwinds all the way up to Edmonton, where we slept under the stars in the middle of the Municipal Airport. Departing Edmonton westward the next morning, the last vestiges of the great plains disappeared, as the lake-dotted forest took over completely. There was no civilization, we just followed the single undulating two-lane road below, west to Dawson Creek under sunny skies. We stopped for gas at Whitecourt and it was at about this time that my radio quit working. It turned out that Grand Prairie, the next airport up the line, had a radio shop, and even more remarkably, they had a replacement oscillator for my radio. They had me fixed and had us on our way in short order. We then overflew Dawson Creek. Dawson Creek is the beginning of the Alcan Highway, which we were surprised to find was paved – for twenty miles anyway. After a gas stop at Fort St. John, we proceeded up the road to Fort Nelson, where we called a halt for the day.

Although it was only noon, we had been flying in and out of rain showers since leaving Fort St. John, and Fort Nelson was the last stop before entering the mountains. For the last two nights we had slept out in the open with cheesecloth draped over our heads for mosquito protection. Since everything was damp and the mosquitoes were really fierce, we spent a miserable night trying to sleep sitting up in our planes with mosquitoes whining around our heads.

The next day didn’t dawn bright and clear, but at least it wasn’t raining. We took off and headed west up the highway toward the mountains. I was flying over the Tetsa River bed that paralleled the road without realizing that the highway had parted company and was climbing the foothills. I came around a bend to find a semi tractor-trailer driving in formation just off my right wing tip. This alerted me to pour on the power and get back above the highway. The highest pass through the mountains is only about 4000 feet, so this was no problem. After cruising uneventfully through the cumulogranite of the pass, the rest of the day settled into a routine of scud running over rolling hills and through narrow valleys with gas stops at Toad River (Mile 419), and into Yukon Territory at Watson Lake and Teslin. The day ended at Whitehorse, YT.

The flight from Whitehorse to Northway, Alaska, took us over huge, broad valleys filled with thousands of acres of dead spruce, past the back side of the coast range (Wrangle Mtns) where in the mountain areas the road map just showed blank white with the notation, “unexplored territory”. We flew over flat glacier-fed river valleys and past steep mountain sides. The contrast was noteworthy; it was either flat or steep, nothing in between. The weather wasn’t bad, just high overcast and some puffy clouds. There is only one intersection in the whole single track of the Alcan which has been the undoing of many a pilot. This is the branch off to Haines, Alaska. We paid attention and stayed on the right road.

This three and half hour leg was kind of stretching my range. After crossing the border, I didn’t want to be forced into landing short of the customs airport at Northway for gas, so when a Gulf station appeared on a straight stretch of road at mile 1176 on the Canadian side, I went down for some more gas. Paul circled once, then continued on. As it turned out, there was a dirt strip next to the road, so I set down on that. I taxied to the end, checked for traffic, then taxied down the road about 500 yards into the gas station, where I topped off the wing tank with six gallons of Gulftane. They thought nothing of it. The trees seemed awfully close to my wingtips landing and taking off; what a thrill. Upon landing at Northway, I was officially greeted by a drunk Indian who staggered up to the plane looking for some fresh wine money. Good to be back in the good old USA. The reported weather up ahead in the pass leading into Anchorage was stinko, so that ended the flying for another day. The couches in the Northway Flight Service Station seemed like heaven that night.

The next day found us heading southeast across the spruce-covered valley back towards the mountains with a gas stop at Gulkana before entering the pass. Scud running again, we twisted and turned through the mountain valleys, just over the tree tops and just under the cloud base, trying to keep the gravel road in sight, and hoping to hell that nobody was coming the other way through the narrow valley. Then right in the middle of the narrowest hairpin turn, I got all puckered up when my engine went rough. My panicky call on the radio to Paul brought back the suggestion that I pull on carb heat. Oh! Is that all? We passed the end of Matanuska Glacier and broke out into the Susitna Valley north of Anchorage.

Paul announced our arrival to Anchorage International as a flight of two, since my 12-crystal “coffee grinder” radio didn’t have tower frequency. The note in my logbook at this point stated, “Logan, Utah to Anchorage, Alaska – 35 hours flight time – 148 US gallons of fuel.” It took six days to do it.

I wasn’t quite as adventurous as it seems. I had a cousin right in Anchorage who had been a stewardess on Alaskan Airlines, and that’s where we headed. After a couple of days, Paul moved on to do some sightseeing before returning home. I wasn’t going anywhere. I was flat broke, and owed Paul a couple hundred besides. On top of that, the big money I dreamed of wasn’t to be had. The environmentalists had stalled the Alaska pipeline, and unemployment was high. All the outfits that had bought C-130’s had gone bankrupt. There were five cargo Constellations sitting on the ramp at Anchorage International that had been repossessed by the IRS from one defunct operator.

After about a week of casting about, I took a job for $4 an hour with the small FBO on Anchorage Int’l where I had parked my plane in the first place. The owner worked two weeks on and two weeks off, flying C-130’s for Alaskan Airlines. I was on my own half the time as the only mechanic. My first job was to straighten a Super Cub that had been modified to carry three people in tandem, but had landed short amongst the tree stumps at some Godforsaken strip with four people in it. The pilot had kept the fuselage from collapsing by jamming a wooden pole between the top and bottom longerons, and lashing the whole thing together with duct tape for the flight home. There wasn’t a straight piece of tubing anywhere in the bottom half of the fuselage. I spent the summer rebuilding this plane, doing 100 hour inspections, and rebuilding magnetos. I moved out of my cousin’s and got a basement room in a boarding house three miles away in town and settled into a routine of hitching back and forth to work six days a week. I lived on a diet of peanut butter sandwiches, oatmeal, canned peaches and cottage cheese, and my food bill only ran $12 a month. I saved money.

Occasionally I flew when I had a Sunday or long weekend off. I only flew six times during the course of the summer, but I made those times count.

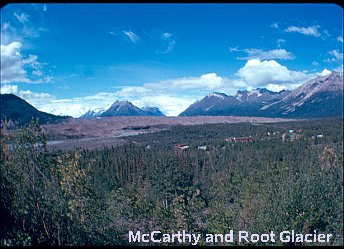

Fourth of July weekend came around pretty quickly. I had met student pilot, Bill Chambers, who was an accountant with one of the oil companies with offices in Anchorage. He had all the light-weight back packing camping gear. I had the plane. We set out together for adventure. Our route retraced the course of my original arrival back northeast to Gulkana, where we headed south, following the broad valley past Palmer. We followed an old railroad right-of-way into the ghost town of McCarthy and landed on a grass strip on a low bluff overlooking town.

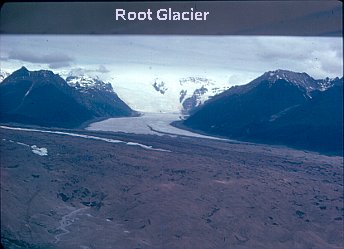

McCarthy is situated at the foot of the Root Glacier which comes oozing out from between the 14,000+ foot Wrangell Mountains about fifteen miles away. McCarthy had existed because of the Kennecott Copper Mill five miles up the right side of the valley next to the glacier. At one time the Kennecott Mill was a complete community in itself, with a copper smelter, company store and worker’s housing. The copper was transported down from the diggings in the surrounding mountains by means of three cable tram ways. The scope of this operation was mind boggling. Bill and I hiked up the dirt road to the abandoned mill and wandered around. There was four feet of ice in the basement of the smelter. There were still WWI posters in the company store. It is said that they hauled 4 million dollars worth of copper out in the twenty years that the mill was operating, but then the grade of the ore declined and the mill was shut down in 1938.

As the Kennecott Mill’s fortunes declined, so did neighboring McCarthy’s with its settler’s shacks, general store and whore house. The town wasn’t totally uninhabited; summer people had taken up residence in some of the abandoned buildings. They had come in by jeep over the rail right-of-way. This was no small feat since the right-of-way traversed three shaky wooden trestles, one of which had already collapsed. This meant a fast ride over the two remaining trestles, and a trip down into the ravine and up the other side for the third.

What do ghost town squatters do for fun on a Fourth of July? Well, they paddle a rubber dingy out into the melt water lake at the foot of the glacier and lasso a chunk of ice for their washtub full of beer. Then they quaff a few while their intrepid oarsmen paddle back across to the glacier and plant a bundle of dynamite with the intent of launching a major iceberg. There is a loud noise and puff of debris, but the ice doesn’t move until it’s ready.

Bill and I camped for the night next to the plane, drank the silty water from the glacier fed stream, and fed the mosquitoes. The next day we leisurely retraced our steps back to Anchorage.

We flew together the next two Sundays, first making a trip south to Hope where the stream was reputedly littered with gold nuggets, and flying over the Portage Glacier. And on the next Sunday, we made another trip north and east, landing at Lake Eklutna and overflying the Knik Glacier and Lake George. It was exhilarating cruising at twenty feet over the maze of rivulets and gravel bars of the broad melt water river flowing out of Lake George.

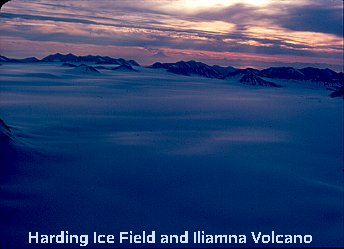

On another occasion I flew alone down over the Kenai Peninsula, and at 7000 feet skimmed over the Harding Ice Field. Here was a mass of ice and snow completely filling the space between 7000 foot mountains, and wherever there were gaps between the mountain peaks, the ice flowed out as glaciers.

One Sunday late in August I ventured up to Fairbanks, landed at the Metro Airport, and hitchhiked out to the University of Alaska for a look around. On the return trip, I followed the route of the new gravel highway under construction between Anchorage and Fairbanks. All was fine until descending from Windy Pass into the Susitna Valley, I found that the ever present cloud base was also descending; right down to the tree tops. A hasty retreat back up the road brought me back to the only pothole-free stretch of road I remembered seeing. It just happened to be on a downhill S-turn. I could tell there were no potholes because there were no puddles. I was right, and the landing was uneventful. I pulled as far over on the shoulder as I could. I threw a sheet of plastic over one wing for protection from the cold mist, sat underneath on the tire, brewed up some soup on my one-burner Coleman stove, made a peanut butter sandwich, and generally made the best of the situation.

Only two vehicles went by in the couple of hours I was there, camped on the road. I waved, and they waved back and continued on their way. An airplane parked on the highway is no big deal in Alaska. Eventually the mist stopped and the clouds lifted a bit. I chocked the wheels with rocks, spun the prop, checked for traffic and taxied uphill around the first bend. A quick turn, a very fast runup and I was off. Fortunately no traffic appeared as I rounded the first turn. I broke ground on the straight-away then followed the road down into the ravine, banking around the second turn as I picked up flying speed and started a climb out, scud running back to Anchorage.