On Labor Day weekend I had Sunday and Monday off. This was enough time to make the most memorable trip of my stay. By now I had a tent of my own, so I was equipped to make a solo overnight trip. I also had finally gotten a crystal for my Narco VHT-3 with Anchorage tower frequency, so I didn’t have to fly in and out on ground control frequency anymore.

Sunday dawned unusually clear. I skirted the north end of the Cook Inlet, flying over a couple of oil drilling platforms in the process. On the other side I entered the Tordrillo Mountains, which form the spine leading out to the Aleutian Chain. The only passage through the Tordrillos to access points west of Anchorage is the twenty-mile long Lake Clark Pass. Normally the mountains are socked in, and flying the pass is like going through a long tunnel. I’d heard tales of a disgruntled grizzly bear who regularly stood on a hillock in the middle of the pass and slashed at low flying planes. I didn’t have this problem; however, as on this CAVU day I enjoyed the spectacular scenery of glaciers cascading down the sides of the pass.

On the other side, my first gas stop was made at the small village of Illiamna, where strong 25 mph crosswinds necessitated a healthy crab right down until touchdown on the gravel runway. And instead of a normal roll out, I ended up sliding sideways to a stop with gravel flying in all directions. I pushed on to King Salmon out in the flat tundra country west of the mountains, where I had heard of a migrating caribou herd to the south. Naturally I had to have a look. The tundra, that time of year, was more water than land, perfectly flat, and only 100 feet above sea level. I never found the caribou out in the endless expanse of tundra, but I chanced upon a gravel bar. I landed there and camped for the night. It was like I was on a distant planet.

In the morning I awoke to a thick veil of fog and the sound of strange stirrings outside the tent. Aliens! Actually I was the alien, and funny ptarmigans, with feathered bell bottom trousers, waddled around the tent in the fog cackling “Lookout, lookout” to announce their displeasure at my intrusion.

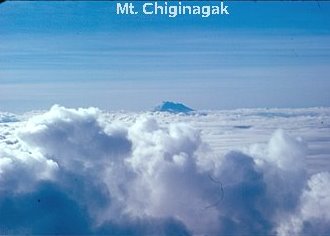

By midmorning the fog broke up enough to take off. Once on top, I spotted a mountain peak to the southeast sticking up above the soup and made a beeline for it.

According to the chart, this was Mt. Chiginagak. I circled the snow-capped 7031 foot volcanic cone and was surprised to find a plume of yellow vapor issuing from the other side just below the top. Beyond were the open waters of the Gulf of Alaska. There was nowhere else to go with my limited range, so I flew back to King Salmon for more gas.

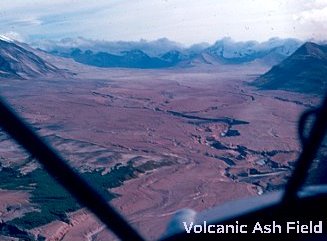

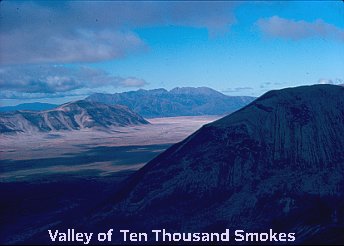

Next stop was Katmai National Monument to the southeast. The last gravel road stops far short of the heart of the park, and the people in the tour buses don’t get to see very much. I left the last overlook far behind, and continued up the Valley of Ten-thousand Smokes which I had heard so much about on the local radio. It seems that Mt. Katmai blew its top off back in 1912, leaving a crater lake up at 7000 feet in what was left of the mountain.

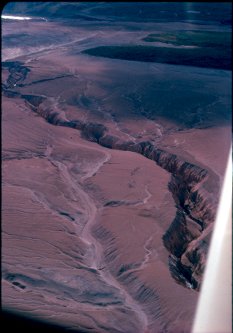

The valley I was now traversing had been buried in beige-colored volcanic ash. The radio ads had extolled that the waste land beneath was so much like the moon that astronauts had trained here. Illegal or not, this was a challenge I couldn’t ignore, to be the only kid on my block to land on the moon. The surface was fairly firm, like a beach at low tide. I left the engine running for a quick getaway and took my small step for mankind. No living thing, animal or vegetable, witnessed my transgression. This was nature’s war zone.

As I continued my flight straight towards Mt. Katmai, the updraft created by the strong tailwind funneling down the valley wafted me right up to the crest with no effort on my part, and then unwafted me equally easily on the lee side. This wouldn’t do, as I wanted to be at 10,000 feet to cross the thirty miles of open water to Kodiac Island beyond. This resulted in my flying in and out of clouds around the rim of the volcano to get back to the updraft side.

The flight across to Kodiac was uneventful. In spite of the three pairs of socks and all the clothes I was wearing, I nearly froze at this altitude. I started descending as soon as I had the coast within easy gliding distance, crossed Kodiac Naval Air Station at 7000 feet, circled the village of Kodiac and landed on the gravel strip there. Kodiac was just a stepping stone and gas stop on the way back to Kenai Peninsula. Although the next ocean crossing was 40 miles, I elected to avoid more exposure to the cold, and crossed at 7000 feet. I was comforted by the fact that there was a pile of rocks exactly halfway across on which to crash land. However, once there, I found that gale winds coming out of the Cook Inlet were inundating the rock pile with waves and that the wind was carrying the resulting froth away. It was at about this point that I dropped 1500 feet in the turbulence in spite of my best efforts to maintain altitude. I just flew the airplane, kept the dirty side down and dreamed about safe and warm places.

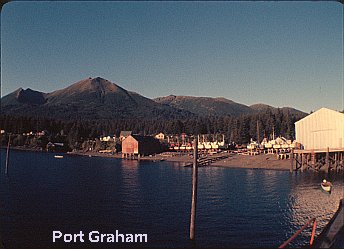

The intact Taylorcraft and the tattered remains of its pilot arrived unceremoniously at the gravel strip of Port Graham on the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula. No sooner had the propeller stopped turning than a horde of Indian children came swarming out of the surrounding forest and completely encircled the plane, pressing their noses against the windows. I was apprehensive that I had just flown this aged aircraft through the jaws of death, only to have it disassembled from around me by souvenir collecting natives excited to a frenzy by the sight of their first white man. Such was not the case. I set about putting up my tent and sat inside with the flaps open eating my peanut butter sandwiches – with an audience. Every time I looked up, one particularly shy little girl would pull back out of sight in the onlooking crowd. It got to be a game, looking up and spying her before she could hide. This place is a particularly warm remembrance.

After eating, they took me on a tour of the waterfront. We walked up and down the wharves, with me in the lead like the Pied Piper and the children following along providing directions and a running narration. All the salmon boats had been pulled up out of the water, the canneries were boarded up and all the white people had gone south for the winter, leaving just the Indians, who lived in shacks amongst the trees between the airstrip and the waterfront. I didn’t see any adults. For all I knew, this was a fantasy world and the children ran the village. They were very happy. No street gangs, drugs, nor Nintendo.

Departing early the next morning, I had time to stop at Homer for gas and still get to Anchorage in time for work. Tough commute.

Alaskan winter was approaching. During the summer the daytime temperature averaged around 60 degrees F. On the occasions when the sun came out, the temperature would soar to 70. It was damp a lot. This being the case, I didn’t want to stick around to see what the winter would be like.

Around the middle of September I gave my resignation and said my farewells. Preflight planning consisted of a party at my boss’s house the night before departure, during which I got very disorientated drinking some kind of Russian wine. I never suspected that wine could have such a high alcohol content.

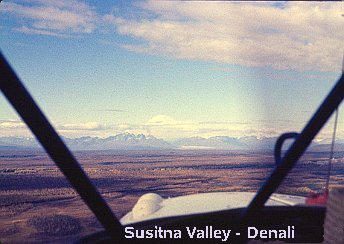

I made an early morning departure from Anchorage, heading north across the Knik Arm and up the Susitna Valley. Heading into the pass through the Alaska Range, a commuter airline Cessna 207 made a routine landing to drop off construction workers on the highway under construction below me. I traversed the Windy Pass in bright sunshine, and landed at Fairbanks Phillips Airport, where I camped next to the Taylorcraft for the night.

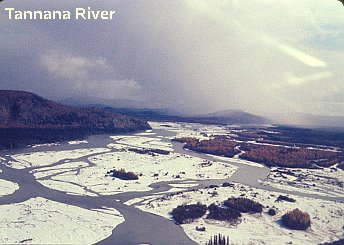

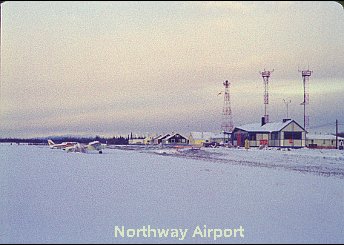

Early the next morning I pulled my camp stool up to the horizontal stabilizer and sat down to my morning mush, then rolled up the sleeping bag, folded the tent, and was off. I followed the Tanana River southwest, flying in and out of snow showers, studying the river’s many gravel bars for possible emergency landing sites. I landed at Northway and camped for the night. In the morning there was an inch of snow on the ground, and on top of the tent.

It was September 21st. Winter was closing in fast. A northbound Piper Cherokee had landed the prior evening and parked beside me; we were the only two aircraft on the airport. In the morning they attempted to start, but their battery had died, so they called into town for a car to come out and give them a boost. They got started, the car left, and then their engine quit. While they called into town for another boost and waited, I hand-propped my trusty A-65 and departed triumphantly.

I followed the Alcan Highway into Whitehorse, YT for a fuel and lunch stop. I was amazed at the low cost of oil there, of all places, so I bought four quarts in anticipation of my next change. I was still running summer-weight oil, but was heading south to warmer climes just as fast as I could. I proceeded on to Teslin, YT. The sky remained overcast. The cockpit was drafty. My hands were freezing in spite of the snowmobile mittens I was wearing. At Teslin I landed on the gravel airstrip, pulled up in front of the radio shack and camped for the night. Teslin is an Indian village situated next to Teslin Lake and the Alcan Highway. The only palefaces were the radio operators and the schoolteachers, who were housed in government-owned houses next to the airstrip.

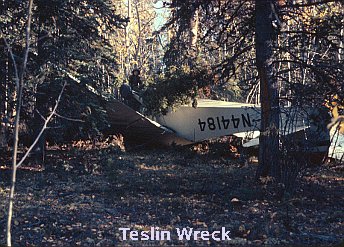

The next morning was cold and damp. I was cold and damp. My sleeping bag was an old hand-me-down which wasn’t very good. The radio operator on duty reported freezing rain further down the road. I determined to push on anyway. I didn’t have a primer on my engine. I primed by squirting auto gas on the air filter with a detergent bottle. It must have taken a half hour of squirting and pulling the prop to get the engine started. At this point I was exhausted from the exertion of getting the engine started and not thinking clearly. I didn’t spend much time warming the engine up. There was no gas available here except pumped from a drum in the back of somebody’s pickup from town, and at an exorbitant price. I had enough to get to Watson Lake if I didn’t waste any. Mistake no. 1: I took off to the north and started climbing even though the engine wasn’t developing full rpm. There was a light cross wind from the right. The highway was less than a half mile away through the spruce trees to the left of the runway. Mistake no. 2: I immediately turned towards the road to pick up my southerly course even though I had only climbed a hundred feet. As soon as I had the wind on my tail, I lost all my meager climb rate and then some. The trees were cut well back from the runway and I had plenty of room to turn back into the wind, but I wasn’t thinking very well, and besides, it was downhill towards Teslin Lake in the direction I was traveling. In theory this was fine, but there was one huge spruce tree dead ahead to complicate things. Mistake no. 3: I had 60 mph on the gauge; I should have briefly traded some airspeed for altitude, but again, I wasn’t thinking very clearly. I kept hearing some instructor’s words from the distant past, “Do not stall the airplane.” Besides, I figured I had enough momentum to brush through the top of the tree with the left wing. Well, that didn’t work.

The next I remember is green going by in all directions in front of the windshield as I cartwheeled through the tree tops. My forward motion was finally arrested by a substantial spruce tree while I was fully inverted, and the plane slid inverted to the ground while the propeller chopped the tree into fireplace lengths as I went down. My body snapped forward, and I cut my lip on the top edge of the instrument panel, not a bad trade, considering that the left rear spar broke free and punched through the side of the fuselage where my head would have been. I was hanging upside down like a fruit bat watching the gas pour out on the ground from the gas cap vent in front of the windshield. At this point my brain caught up with recent events, and I realized that I had lost control of the aircraft. I let go of the control wheel, pulled all the circuit breakers, unbuckled the seat belt and fell on my head, then kicked the door open and exited.

As I started walking through the woods back to the airstrip to let them know I was all right, I heard sirens and people approaching the crash site from behind me, so I went back. There must have been three or four people crawling all over the wreckage looking for the body. There was no body! They were very agitated. I walked up behind them and asked if they were looking for me. The local Mountie soon arrived and provided levity by commenting, “I see you’ve been cutting firewood without a permit, Ay.”

The upshot of all this was that I had to wait for three days for DOT crash investigators to fly up from Edmonton before anything could be touched. The local authorities hired someone to guard the wreckage around the clock. The guard built a campfire and slept on the ground next to the plane all night. These people are real professionals when it comes to crashes. Imagine the all the experience they must have. They told me of a recent incident of a Cessna 180 which landed on the highway and had its tail torn off by a speeding semi before the pilot could get it clear of the road.

One of the radio operators took me into his house and gave me a spare upstairs bedroom while we waited for the investigators. I woke up in a cold sweat during the next three nights with nightmares of trees leaping out of the ground to grab me. I amused myself during one day by helping my host carve up the moose he had just bagged. This was wrapped and stored in the community locker next to the airstrip, but not before we each had a T-bone from it.

When the two investigators flew in, I admitted to every kind of idiocy, signed my name, and they released the wreckage. I realize now that what happened is that my carburetor iced up again in the damp air. If I had pulled on carb heat and continued climbing out straight, the carb would have eventually cleared, and I would have been all right. But then again, I was exhausted from pulling on the propeller, and my brain just wasn’t functioning. Many willing hands helped to unbolt the wings and hack a path through the woods back to the airstrip. All the parts were parked beside the cold storage locker next to the airstrip. The fuselage looked surprisingly intact, making me a believer in chrome moly tubing construction. I promised to return in the spring to retrieve the remains, and boarded a south-bound bus at the general store out on the highway.

Once a week the bus traverses the length of the Alcan Highway. It was the bus ride to hell. The back was curtained off, and a spare driver slept back there. It never stopped, and pitching over the gravel roads, I couldn’t sleep. This lasted for about three days until I had to lay over one night in Calgary for the next connection. Eventually I was deposited in downtown Logan, Utah at around 3 AM one morning. I gathered up all my belongings and trudged up towards the USU campus where one of my AeroTech classmates, Mark Wolf, and three roommates had an apartment off campus. Their door was locked, and I didn’t want to wake them up. I don’t know who had the apartment next door, but their door was unlocked, so I went in and sacked out on the living room couch until a more reasonable hour.

In the ensuing days I retrieved the Toyota Corona that I had left with a married USU student three months earlier. The Volkswagen bus that I had also brought from Connecticut was left parked in the apple orchard of the couple I had previously boarded with in North Logan, and I drove the Toyota back to Massachusetts to my parents’ house to visit. After a couple of weeks I drove back to Utah to look for work. The only thing I could come up with was a temporary job for three weeks as a floor sweeper in a sugar beet refinery just over the line in Idaho. I worked all night, and in the morning there would be a thick coating of coal ash all over the cars from the refinery’s boiler plant. The spilled syrup and molasses that I washed down the drain ran into a nearby stream.

The fall harvest of sugar beets had all been refined by the time the USU Christmas break rolled around, so I offered to drive Mark Wolf to his home in West Virginia for the holidays. While there, we had a couple of days during which we did some cave crawling before I pushed on to Massachusetts. I spent the winter of ’70-’71 with my parents, and helped my dad repair watches, as there was no other work.