As May 1971 rolled around, I decided the time was right to go back to the Yukon to retrieve my airplane. One of the Boston radio stations had a service called “Travelers Friend” which broadcast a list of people looking for rides and travelers looking for riders. I connected with a pair of hippies going to Arizona in a beat up Dodge Dart. My mother took me to meet my ride at the prearranged place, the parking lot of a Marriott motel out on Route 128. The three of us took turns driving, around the clock. The owner of the car was a Vietnam vet who got into heated discussions with the other passenger about using his Army job training in blowing up bridges and whatnot for the violent overthrow of the U S government. Mostly I just cringed in the back seat. When I let on that I was a pilot, they suggested that I go to work for Air America, flying cargo planes full of dope around Central America. They obviously knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t. I jumped ship in Flagstaff in the middle of the night. This was their route’s closest approach to my destination. My share of the gas bill was something like $18. I slept in the bus depot and in the morning took the first bus north.

Upon arriving in Utah, I retrieved my Volkswagen microbus out of the apple orchard where it had been left the previous fall. I had to buy a new six volt battery for it. The tires were fair, the brakes were pretty bad, but the emergency brake worked. It wouldn’t pass inspection, so I didn’t bother to register it either. It had an expired Connecticut plate on it. The population was so sparse north of Utah, I didn’t figure anyone would notice. I got as far as the town line before the Utah Highway Patrol pulled me over. “Where you going, boy?” When I blurted out that I was only going as far as Canada, a neon sign must have lit up in his head, “Pinko-Commie draft dodger.” They impounded my bus. They had a tow truck drag it back to Logan and put it in a locked compound. I couldn’t go near it. I couldn’t post bail. I had to wait three weeks to appear in court and pay a fine. Then I had to fix the damn bus, get it registered and inspected. Was the plane really worth it; this was getting expensive and time consuming. But I got even, for while I languished in Logan, a gas war broke out. Prices dipped to 23 cents per gallon from their usual high of around 30 cents. I gathered up three empty oil drums and headed down to the neighborhood gas station and asked for a fill up. I stopped at 96 gallons, as the tires were going flat from the weight.

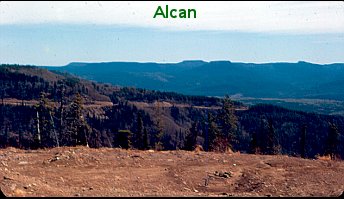

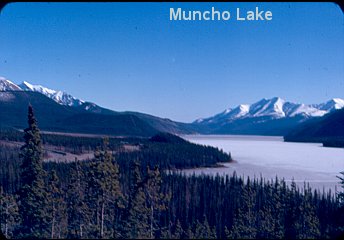

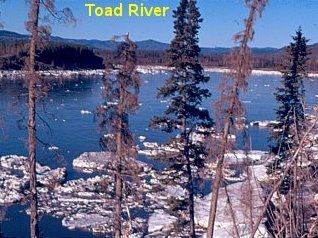

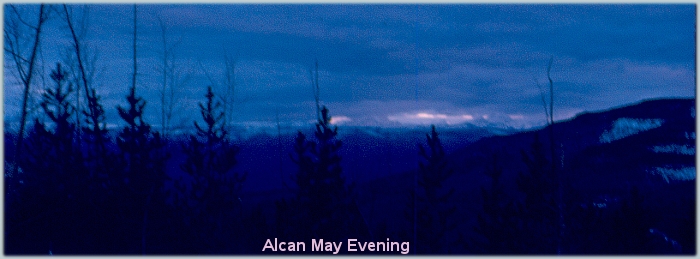

I headed to Canada. The operation went something like this. The first smaller drum started out on the self over the engine with a rubber fuel line going directly to the fuel pump. When that drum emptied, the hose was moved to an upright drum in the middle of the bus. When that drum burned down to a manageable weight, it was moved to the self over the engine. And so it went for the next two thousand miles. I crept up on all railroad crossings as my brakes still weren’t the best. I slept on the front seat. Three days of hard driving got me to Teslin, Yukon Territory. The weather had remained good, so the Alcan Highway was in good shape, but the bus filled with dust because the body was rusted through all the way around at floor level.

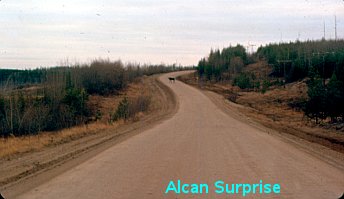

The Taylorcraft was just as I had left it the previous fall. I set to work immediately. The empty oil barrels were discarded, and the A65 Continental engine was removed and put inside the bus in their place, along with the tail feathers and the left-hand landing gear. The fuselage was slid up onto the roof of the bus tail first and lashed down. Horizontal 2″ x 4″ stakes were shoved between the floor and frame on the left side to support the right wing against the side of the bus. The driver’s side door was no longer usable. The side mirror was extended out so that I could see to the rear. I started disassembling the left wing, but gave up as there was so little left to salvage. I took some ribs and fittings and abandoned the rest. After a good night’s rest, I started back down the Alcan.

During the couple of days involved with the preparation for hauling the airplane, I stayed with the same couple who had been so hospitable the previous fall. On the day I was leaving they had left early in the morning on an overnight shopping trip up to Whitehorse, so I was left to lock up on my way out. I got thirty miles down the road before I realized I’d left my jacket with my wallet in it back at the house. I figured clearing customs with an airplane on my roof could be kind of tricky without any identification, so I pulled into a turn off to turn around. There I met a stranded family with a broken transmission waiting for parts to arrive on the next bus down the Alcan a couple of days hence. They asked me to bring back a loaf of bread. I left my fishing rod with them so they could catch something to eat until I got back. There was a pond right beside the road.

Back at Teslin, I had to go all over the village to find someone who had a master key to the house and let me in. I set out again, with my jacket and wallet this time, delivered bread to a very thankful family, and pushed on. With all the backtracking, I only made it to the vicinity of Watson Lake that night, where I pulled into a picnic area and slept on the front seat of the microbus.

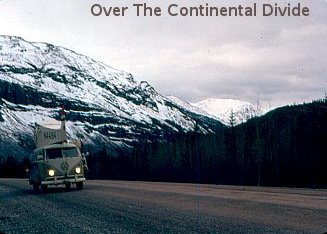

It snowed about an inch during the night, and that was enough to turn the highway into a mud run. In addition, the VW engine was running very hot. Crossing the continental divide was severe punishment. One distraction from the monotony of the drive was watching all the occupants of approaching automobiles go slack-jawed and then turn and point as I went past.

Arriving at Fort Nelson, I came in limping with a very sick engine, and parked next to a diner on the edge of town. I pondered my fate. I consulted by long distance telephone with my good friend Charlie Souliere back in Logan, Utah, but as for getting help to me, I might as well have been on the edge of the universe. I finally decided that I would have to fix it or grow old and die right there.

Mercifully the weather stayed warm and dry. I set to work. The back bumper had been welded on, due to rusted bumper brackets. I hacksawed the middle third section out, and proceeded to unbolt the engine and drop it on the ground. This was not fun; everything was caked with an inch of mud, and the mosquitoes were ferocious. I dragged the engine out into the open and proceeded to operate on it on top of an old wash tub I’d found. After pulling the cylinders off one side, I discovered two pistons with holes burned through them. This was not encouraging.

People at the diner told me about a junkyard a mile down the road, and I went for a walk. There may have been a junk yard at one time, but there wasn’t anything there now, except for two or three engines laying on the ground, one of which happened to be a Volkswagen. I went back that night and stole two pistons out of it. Now I was getting somewhere.

While I was completing reinstallation of the engine, a native strolled by and shared his wine with me, so it shouldn’t have been any surprise that the engine when finished didn’t run any better than before. I started out anyway and got twenty miles, to where the road dipped into a hollow. I couldn’t get up the other side. I turned around and couldn’t go back either. I was obviously still operating on only two cylinders, and I only had thirty-six horse power to begin with. The way back was the more gradual incline, so I lurched my way out of the hollow by repeatedly flooring the peddle and popping the clutch. I drove the twenty miles back to the diner, and sat in desperate contemplation. I started checking things. When a couple of kids walked by, and I asked one of them to hold the coil wire while I ran up front and turned the key. The yell assured me that I had plenty of spark. Eventually I figured out that two spark plug wires were switched. No more wine for this boy.

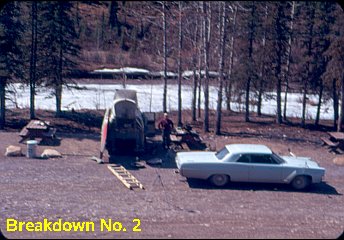

I headed south once more after having spent three days in Fort Nelson. Things went fine until eighty miles short of Dawson Creek when the engine started clanking. I nursed the microbus into a picnic area and sat cold, dirty and discouraged. About this time a big sedan from California pulled in towing a 22 foot travel trailer. It was just an old guy and his dog headed for Alaska. He was naturally curious about the unusual assemblage of parts. I suppose it looked as though the crash had just occurred right there. After I related the story of my woes, he decided that we ought to fix it. Oh, sure! Well, it just so happened that he had just about every tool imaginable packed in his trailer, piston ring compressor, torque wrench, you name it.

Out came the engine again. We disassembled it and spread the parts out across three picnic tables. We weren’t too fussy about the tables, as DOT workers were in the process of repainting them anyway.

All the parts were cleaned in a washtub of gasoline. The problem turned out to be a failed main bearing and a chewed up crank. Imagine my surprise when a call in to Dawson Creek located a new crank. My new-found friend unhitched his trailer and provided transportation into Dawson Creek and back. I provided the gas. In short order we had the old bus running like new.

At this point I had been on the road several days from Teslin, and had two sessions in the mud and dirt under the microbus behind me. I wasn’t in any condition to present myself to more civilized regions down the road, so I prevailed upon my savior to let me use the shower in his trailer. Now I was restored, physically, mentally and mechanically, but I wasn’t going anywhere just yet. My left rear tire had gone flat while sitting there, and no amount of grunting would free the lug nuts. I limped to a nearby gas station where an acetylene torch was available. A little heat loosened the lug nuts and I changed the tire. My new friend continued north, and I pushed on to the south.

Before I got into Edmonton, the bus started shaking and clunking. All the lug nuts had fallen off the left rear wheel, save one. I stole one lug nut off each other wheel to tighten this one up, and continued. Some of my tires were getting quite thin, so I bought a couple of used ones in Edmonton for five dollars apiece. They had a little tread on them, which is more than I can say for the ones I replaced.

I was on level ground now, and progress was pretty good, until half way between Edmonton and Calgary, when the engine started clanking again. I pulled off the main road onto the shoulder of a dirt side road. I was tired, discouraged and broke. Canadian citizenship was beginning to look like an alternative. I hiked up the dirt road to a farm house and borrowed their phone to call Charlie in Utah again. By now it was into June and he had just finished his final exams at school. He would be right up. I gave him directions to where I had a tow bar stored in Logan. Only one problem, though; he didn’t have any money either. This is a small matter for a resourceful individual. He went out that night to a gravel pit and siphoned the gas out of half a dozen ready mix trucks and filled a drum in the back of his 1960 Chevy station wagon. He brought another friend along to share the driving and drove straight through the night. After all, what are friends for? There was one other problem, though.

About this Chevy wagon: Charlie had bought it with 70,000 miles on it and a supposedly bad automatic transmission. It now had 140,000 miles on it; the transmission was still going strong, but the engine was down to seven cylinders. Charlie raided every junk yard between Utah and Alberta trying to get the parts to solve his problem. By the time he got to me, he had spare distributors, spare spark plug wires, spare carburetor, just about a whole spare engine except for a short block, but was still only running on seven cylinders. I had had about two day’s sack time in my tent beside the road by the time he arrived, so I was thinking pretty clearly. I pulled the valve covers and watched the engine turn over. Sure enough, one push rod wasn’t pushing. I pulled the rod out and found it had collapsed. A trip to a nearby Chevy dealer provided a new push rod for only about three bucks, and that fixed it. It’s nice to win one once in awhile.

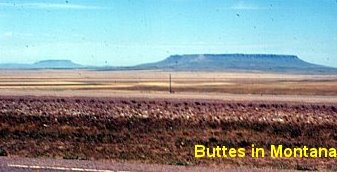

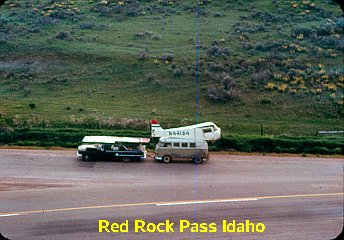

We streamlined the bus a bit by taking the wing off the side and putting it on the roof of the Chevy. The bus was hitched up to the back of the wagon with the tow bar, and we were off. We raised a few eyebrows when we pulled up to the customs booth in the middle of the night, but clearing wasn’t too difficult once I told Charlie to just shut up, and stop running on about all our adventures, family history, our ancestry, etc. Charlie liked to talk nonstop. We had to cross the continental divide three times. For this we carried jugs of water to splash on the radiator on the long upgrades to keep the engine from boiling over. Once, when pulling through a small village in Montana, we heard a small boy on the side of the road exclaim, “Wow, it’s a helicopter!” We got back to Logan, Utah without further incident.

I tore down the microbus engine once more, and found a rod bearing gone. I tried replacing it with an oil-soaked leather strap, but that didn’t work. By now I figured the bus was all used up, and I sold it for junk.

I still had to get to Massachusetts. I had planned to be away only two or three weeks, and now it had been nearly two months. Charlie loaned me his car. He would get a ride east with someone else in the fall and get it back then. We pulled an all-nighter and built a trailer for the fuselage. Charlie was renting a shop on the edge of town, and it was set up as a welding shop. We salvaged some chrome moly tubing from some old engine mounts for a frame, and stole the front wheels and spindles from an old Plymouth someone had left parked outside. The Taylorcraft wheel spindles were cradled in wooden blocks, and the tail spring mount was bolted to the tongue. The Taylorcraft was part of the trailer.

I headed east by myself with all my belongings in the back of the wagon and the Taylorcraft dragging along behind. At a rest area in Nebraska, a reporter stopped and took my picture for his local newspaper. I decided to cross into Windsor, Ontario to avoid the toll roads in the Midwest. At the customs station the Canadian customs agent insisted that my trailer looked wider than eight feet. I assured him it wasn’t, although I knew it was really two inches over. There was a tense moment while he walked to the back and paced off the width, but he came back and agreed with me. I resumed breathing.

In order to cross back at Niagara Falls, I had to drive through the center of Hamilton, Ontario right at noontime. It just so happened that Prime Minister Trudeau was arriving at that very same time. There were two traffic lanes each way, with each lane barely eight feet wide. I was weaving from lane to lane, trying to dodge the protruding manhole covers to protect my bald tires, and both sides of the street were lined with people shoulder to shoulder, awaiting the prime minister’s motorcade. Just as I passed through the center of the city, I saw his helicopter pass overhead. I wasn’t looking for notoriety. I just wanted to vanish, and I did, out the other side of the city, just as fast as I could.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, except for the constant fear of a blowout on the New York Thruway. The plane ended up in my parents’ back yard in Massachusetts. My dad said it would never fly again, and being broke and out of work, I didn’t have any grounds for disagreement.

Eventually I bought land of my own in Maine, and set about building my own house. I started out by building a 26-foot diameter geodesic dome, because it didn’t take a lot of materials, and I could prefab the shell in triangular pieces in my parents back yard. That worked out pretty well, so I built another 39-foot dome for a workshop. My wife didn’t appreciate that the workshop was bigger than the living quarters, so I then built a two-story connector between the two domes. Finally I built another 39-foot dome as a detached four-car garage. In between dome building, I managed to rebuild my Taylorcraft into a Model 19.