These are the graves of my father, George Kenneth Patten and his brother – my uncle – Irving Bruce Patten. They are buried together in the military cemetery in Epinal, France.

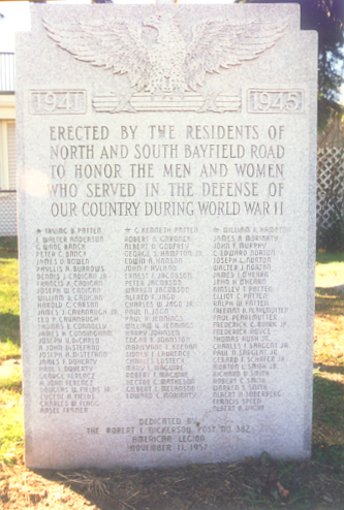

My name is Bruce Kenneth Patten. I was named for these two men whom I had never met. I didn’t know my real name until I was 13 years old. My mother had remarried twice in rapid succession following the death of my father, but had never changed my last name, so I had been using the name of my second step father. She finally had to tell me because I had been selected to unveil a new veterans’ monument on the end of the street in Quincy, Massachusetts where my father and his four brothers had grown up. In 1957 I rode in a Veteran’s Day parade in the back of a jeep with three army colonels. I stood facing all the assembled people while the speeches were being read, then I was motioned to walk up and pull the covering off the monument.

There inscribed were the names of all the men from North and South Bayfield Road who had served in World War II, and there at the top, the names of my father and uncle, the two who didn’t return.

Thus began my quest. I knew that someday I wanted to go to my father’s grave, but I would have to do it on my own, as my parents never had enough money. My mother had told me that his plane had been shot down by flak over Belgium. After joining the American WWII Orphans’ Network, I started finding new sources of information, including the Missing Aircrew Report from the National Archives, a researcher in Switzerland, my only surviving uncle, the Individual Deceased Personnel File from the U. S. Total Army Personnel Command, and the Internet.

The five Patten brothers went off to war: Irving as a B17 bombardier, Ainsley in Army ordinance, Kenny as a B24 bombardier, Elliot on an ocean going Navy tugboat and Ralph working at the Bethlehem Hingham shipyard. Ralph stayed behind to care for his parents, then in 1946 he joined the Army and served in Korea.

Irving B. Patten was a rugged outdoors man and an avid skier. He joined the Army in January of 1941, and served in the coast artillery and then with ski troops near Tacoma, Washington. In late 1942 he transferred to the Air Corps and ended up as a bombardier in the 12th Air Force in North Africa. He was assigned to the 99th Bomb Group based at Oudna, Tunisia when he had a long range mission to Augsburg, Germany on October 1, 1943. His squadron became lost above the clouds and overflew eastern Switzerland. They came under enemy fighter attack in the vicinity of Feldkirch, Austria, and turned back south, as the target area was socked in by clouds. The German fighters continued the attack into Switzerland. The plane in which Irving was bombardier was damaged by head-on fighter attacks. After passing the Swiss fortress of Sargans on the Rhine River, a Swiss anti-aircraft battery at Bad Ragaz opened fire on the formation of fifteen or so aircraft. They zeroed in on Irving’s plane, Sugarfoot, as it was trailing a contrail of smoke from one engine, making it easy to track. The Swiss had a habit singling out crippled American aircraft for attack. They scored a direct hit on the front of the airplane. Only the top turret gunner and two waist gunners managed to bail out before the tumbling airplane slammed into the side of a mountain.Bad Ragaz

Irving was buried by the Swiss in Bad Ragaz, Switzerland. On Memorial Day 1944, his body was moved to the American cemetery at Munsingen, Switzerland. After the war all the American war dead at Munsingen were exhumed and either sent home or reinterred in the American military cemetery at Epinal, France.

G. Kenneth Patten was in the first class in the new North Quincy High School, where in 1934 he was captain of the wrestling team. One of his team mates was Charles Sweeney, who was to become pilot of the aircraft that dropped the second atomic bomb, August 9th on the city of Nagasaki. They graduated in 1934. Kenny, as he preferred to be called, went on to earn an associate degree at Wentworth Institute, whereupon he worked as a designing draftsman for General Electric in Lynn until called up for active duty on February 28, 1943. He received his wings and commission at Nashville TN, and completed his training at Santa Ana, CA; Victorville, CA; Tuscon, AR; Blythe, CA and Pueblo, CO. My mother was a cadet groupie; she and a troupe of other young wives followed their spouses from base to desolate base, living out of run down motels and guest houses. There were good times, too, such as leave time spent together at Lake Arrowhead resort and horseback riding together at Tuscon. Ken was sent to the newly forming 491st Bomb Group at Pueblo, Colorado.

I was startled to discover the official history of his unit, the 491st Bomb Group, on the Internet, especially because there was mention in there of my father by name. He had been trapped in the nose turret of a flaming B 24 on his 28th mission, and gone down with the plane near Hanover, Germany on November 26, 1944, just five months to the day after I was born.

My father’s unit was the 853rd squadron of the 491st Bomb Group. His aircraft was The Moose, piloted by Lt. Warren Moore. The navigator was Lt. Ross Houston. The navigator and bombardier got to their station by crawling under the flight deck on a catwalk beside the nose wheel well. It was common for the bombardier to also man the nose turret. Ken was well suited for the cramped confines of the turret, as he was only 5′ 3” tall.

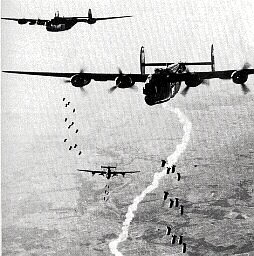

On Sunday 26 November 1944 the storm front that had been stationary over central north Germany for much of the previous week was clearing. The Eighth would be after four major targets in Northern Germany. The entire 8th Air Force minus 3 bomb groups would be involved. This meant 24 bomb groups, 15 fighter groups and 3 scouting groups. Total allied strength was 1070 aircraft. The objective for the 491st was the one remaining oil refinery still in production at Misburg. The 491st Bomb Group had been over Misburg before, on September 12th, when two aircraft were lost. But lately the Group hadn’t been losing any airplanes. Still, there were some who noted that the strike at Misburg would require deeper penetration into Germany than any of the other targets for the following day. The Group Intelligence Officer had established that there was a large number of German fighters in the area adjacent to the target, and that they had been acknowledged through intelligence channels as still having quite an attack potential. They had been rather inactive for a while, and 8th AF believed that they were being held in readiness for one big effort.

The Fortresses led the raid, followed by Squadrons of B-24s from the 389th, 445th and 491st Bomb Groups, with High and Low Squadrons all jockeying to remain in tight defensive formation. Several B-24s aborted and timings began to go awry, which was bad news for the 491st flying at the tail end of the bomber stream. Over the North Sea the 389th and the 445th turned late, spreading the Divisions over an area stretching for forty miles instead of twenty and effectively rendering the escort ineffectual. The B-24s were on their own for some 30 minutes to Misburg. It was my father’s misfortune to be in the last squadron of the last bomb group of the entire formation.

As the Liberators of the 491st Bomb Group approached the target, a large concentration of enemy fighters appeared in the distance to the east. All the remaining Allied escort fighters took off in pursuit, leaving the bombers unprotected. Then 30 miles short of the target, the navigator in the lead bomber of the middle squadron of the 491st Bomb Group accidentally brushed against the bomb toggle switch in the nose of the bomber.

The squadron had been briefed to drop their bombs with the leader, so all 30 tons of bombs from the middle squadron dropped into empty fields. Rather than continue flying through the hail of flak, the middle squadron pulled out of formation to bypass the target. This left a huge gap between the lead and tail squadrons. My father’s squadron was now isolated from the other squadrons in the bomb group, which was in turn, isolated from the other bomb groups. They flew beyond the target, and wheeled into the big turn, starting their bomb run over the town of Wittingen, 16 miles northeast of Misburg.

The heavy flak stopped abruptly, as if by prearranged signal, and another force of 50-70 enemy fighters launched a company front attack enmass of 7-10 abreast on the tail end squadron. Some fighters hit from 5 o’clock, others from 7 o’clock. The second pass took out the two B-24s of the high right element, piloted by Stevens and Budd. Stevens had been flying his first mission since 20 June, when he crashed at Dover. Just after the first fighters hit, his engineer, F/Sgt. Joseph L. Boyer, yelled, “They’re coming in again!” An instant later he was killed by a 20 mm shell, his body falling out of the open bomb bay doors. Moments later the plane exploded. Stevens was blown clear and again survived.

Moments later, just as the squadron was approaching the release point, Moore and Stewart were hit badly but managed to make it over the target before going down. The Moose piloted by 1st Lt. Warren Moore was hard hit on the first pass, which left #2 engine burning, the bomb bay on fire and the intercom and hydraulics out. The tail gunner and two waist gunners in the rear section were killed, riddled by 20 millimeter shells. Because the fire had not reached to the wing tanks yet, the aircraft proceeded to the target. Sgt. Hawkins climbed out of the top turret. As the hydraulic system was all shot out, he went through the fire and opened the bomb bay doors manually. He either was overcome by flames and fell out or his parachute burned and didn’t open. He didn’t survive.

Their load of bombs was dropped on the target, then pilot Moore gave the bail out signal. He hadn’t had time to set the auto-pilot so he held the ship level while the remaining crew bailed out. Then he jumped, himself.

Bombardier George K. Patten was manning the nose turret. The nose turret doors were normally left open whenever over the target, so that if anything happened over the target, the nose turret man could be gotten out in a hurry. This was the most difficult position to escape from in an emergency. In the confusion of battle, he tracked a German fighter to the left without closing the inner turret door, and the turret jammed in the extreme left position. When the bail out signal sounded, navigator Ross S. Houston opened the outer nose doors and saw the turret sitting sideways. Finding the interphone damaged, he attracted Ken’s attention by pounding on the turret and signaled him to straighten the turret so he could get him out. Ken acknowledged. Seeing that he was having trouble straightening the turret and believing that the turret system was also damaged by the explosions in the rear of the plane, Houston worked frantically to straighten the turret with a hand crank provided for such emergencies. The plane was out of control now, making working with the turret harder and harder, and fire was up to the cockpit. Houston had to leave when the ammunition in the top turret started to explode. Seconds later the whole aircraft exploded over the town of Gehrden, several miles southwest of Hanover. The entire 853rd squadron of 9 B-24’s had been shot down. Of the 84 men of the 853rd, 50 were dead, and many of the rest were badly injured.

Friedrich Kirchhoff, then a 22 year old soldier on home leave in Gehrden, witnessed the bail-out of the crew with unopened parachutes. About 1000 feet from where he stood a part of an engine with the propellor still whirling came down in a garden. As a soldier he reported to the Gehrden police and went with them to the crash site. The policeman Remmers and the mayor Von Reden were already there. Kirchhoff saw the bodies of the airmen.

Georg Weber, as a 14 year old apprentice auxiliary policeman with the town of Gehrden, also had to go to the crash site, with his boss mayor Von Reden. For the first time in his life he saw the bodies of dead people. They were scattered on a field, most of them buried a foot deep in the soil. Thanks to their heavy overalls their bodies were intact. The Germans collected the dogtags from their wrists. The mayor had the bodies laid out on straw in a shed on the Franzburg estate, where later Germans came to collect them.

Navigator Houston bailed out of The Moose through the nosewheel door. He later reported, “After delaying the opening of the chute, the noise of the fighter combat and the B-24’s engines ceased. I pulled the ripcord and with the jerk of the chute opening, I remembered the lectures about always having our harness adjusted tight. It must have been the looseness and the amount of clothing that caused the harness to pull tight, too high on my body.”

“The quietness of my descent sobered me to the point, that with three missions to go, I wouldn’t be home for Christmas. The next thought was ‘Where am I in Germany and what kind of reception would I get on the ground’. It was a clear day and I saw the ground getting closer. It was good that I didn’t know how fast, as I would have braced myself, causing myself possible injury on landing. In contrast, I hit the ground before I knew it and doubled up like an accordian. The wind was blowing so hard, it took my chute and dragged me across the frozen plowed field ripping my flight parka on the left sleeve to shreds. The dragging motion stopped and allowed me to stand up and unfasten my harness which was still unbearably tight.”

“I then realised that some German civilians had collapsed my chute and were running off with it, leaving me standing in an open field trying to orient myself.”

“I wasn’t alone very long, as a German soldier was running across the open field towards me. With caution he approached, not knowing whether I was armed or not. While searching me he relieved me of my watch and escape kit and directed me to go toward a dirt road a short distance away. We walked down this road a short distance with the soldier behind me with my hands raised. An elderly man with a cane walked toward us and asked whether I was Yank or British. With the answer of Yank, he swung his cane and hit me in the head, causing an open cut above my left eye. The scar is a reminder of that incident.”

“The guard and I entered a small town, where I met my Co-Pilot, Bob McIntyre, still carrying his chute, and being escorted by another German guard. My guard stopped at a first-aid station, where they put some white powder on the cut and stopped the bleeding with a piece of adhesive tape. While we were going through town, the villagers took pictures, shouted and spit on us. We were taken to a shower room at a garrison outside the town, where we saw our radio operator, Joe Rimassa, and other downed fliers. We were searched again and our shoes were taken from us.”

“That night, we were taken to town by truck to another military facility in Hannover, where we saw the devestation of that city. Upon arriving there, we saw my Pilot, Warren Moore, who was burned about the face. We were given some hard sausage and bread to eat, which was the first food we had since breakfast. After giving the German officer my name, rank and serial number, my interrogation included being informed by him the names of the crew that did not survive the ordeal. We complained about being kept in a room with the windows broken out and the Germans reminded us that we did that.”

Pilot Moore had also bailed out: “As I was nearing the ground in my parachute I saw a group of people following my decent path. When I landed I was circled by about 15 people. I think the reason they didn’t rush me was because they may have thought I had a gun. Fortunately two soldiers drove up and took me in their truck into the city and placed me into a jail cell. When it got dark and during the blackout they took me by street car to a building on the outskirts of the city where all the other captured crew members were. From there we were all shipped to Nuremberg to the interrogation center.”

“We were placed into individual cells with no windows with a slot in the door to push the food through. Our toilet was a bucket. On the second day it was my turn to be interrogated by a German officer. When I entered his room the first thing he said was ” you can’t tell me anything”. “I know the bomb group you were with, I know the target, I know your altitude and I know the type of bomb you used”. He was very proud of that and liked to brag about it so I was sent back to my cell. After a day or two we were put on the train and sent on our way to the Stalog Luft #1 a camp across the North Sea from Sweden.”

“While in prison camp our barracks had bunk beds 8 across and three high with a straw mattress. Once a week we were sent to the showers and we treated each other for lice. Prison camp was boring and we were not mistreated if we behaved. If we were to open a window during a blackout they would shoot at us. The camp consisted of both English and American officers. There were Russian prisoners there also but they were not allowed in our compound.”

“They were given the less desirable chores (like empting the toilet buckets) and they did not ‘mix’ with us. Once in a while we would receive a Red Cross food parcel and those of us who did not smoke would give the cigarettes to the Russian prisoners. There was a library with books written in English which helped us spend our time. The food was eatable and consisted of potatoes, cabbage, and a dark bread (some said it had sawdust in it). Once in awhile we were fed horse meat which we looked forward to. Near the end of our prison term the food was very bad, but of course, the German people we not eating well at that time either.”

“I spent the first 4 days in the hospital to have my burns treated. The doctor was an Englishman. Some time about May we knew the Russians were on their way to Barth because we could hear the cannon sounds and the fighting. I think about May 15 we all woke up and noticed that all the guard towers were empty. The first thing all the POW’s did was to knock down the guard towers and tear up the barb wire fence. I think after the Russians arrived we were there for 3-4 days until the US airforce flew in B-17’s to an airfield next to our prison. We were all then flown to a rehabilitation camp on the coast of France where we stayed for about a week for debriefing before we were sent home to the States by boat.”

“When we arrived in the States we were given 2 weeks off at an ocean tourist resort in Malibu, California. We were then sent to a refresher school of ground and flight instruction. We were being retrained to be sent to the war in the Pacific. Thankfully the war ended and we didn’t have to go.”

Back home the letters from overseas stopped after November 26. Then on December 27, my mother received a telegram from the government, “THE SECRETARY OF WAR DESIRES ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET THAT YOUR HUSBAND FIRST LIEUTNANT GEORGE K PATTEN HAS BEEN REPORTED MISSING IN ACTION SINCE TWENTY SIX NOVEMBER OVER GERMANY IF FURTHER DETAILS OR OTHER INFORMATION ARE RECEIVED YOU WILL BE PROMPTLY NOTIFIED=DUNLOP ACTING THE ADJUTANT GENERAL.

She held out hope that he would be found alive. The letters back and forth to the War Department commenced, searching for any word. There was false hope when the wife of Bob McIntyre, the copilot, received a Red Cross wire reporting Bob a prisoner of the Germans, and Ross Houston, the navigator, sent a message home by short wave radio. The letters back and forth continued into 1945. The war in Europe ended, but still there was no word. There never was a definitive finding by the War Department as to whether my father was dead or alive. My mother was left with uncertainty until the surviving crew members came home and could relate what happened.

The Germans buried my dad in a group of 19 unknowns in Seelhorst Cemetery in Hanover on December 4, 1944.

In April of 1946 the remains were identified by the Quartermaster Corps from body size (5’-3”), dental records and 1st Lt. bars attached to clothing remnants. He was then reburied in the US Military Cemetery Neuville-En-Condroz (Plot K, Row 12, Grave 292), located nine miles southwest of Liege, Belgium on April 23, 1946. Irving B. Patten had previously been buried in Munsingen, Switzerland (A 1 4) and then reinterred in Epinal, France (B -45 -21). In June of 1949 my grandparents requested that G. Kenneth Patten’s remains be permanently interred beside or as near as possible to the grave of his brother, Irving. Kenny’s remains were subsequently interred in Plot B, Row 42, Grave 12 in November of 1949. Apparently, they moved another body to get him this close to his brother.

No one from the family had ever gone there. I felt I had to. In September of 2003, my wife, Cheryl, and I finally had the time and money to make the trip. It was a long day of nonstop travel from central Maine to Epinal, first by car and bus to Logan Airport, a night flight to Charles de Gaulle Airport, a train into Paris, another train to Nancy, and yet a third train to Epinal. The first full day in Epinal was spent touring the city in intermittent mist.

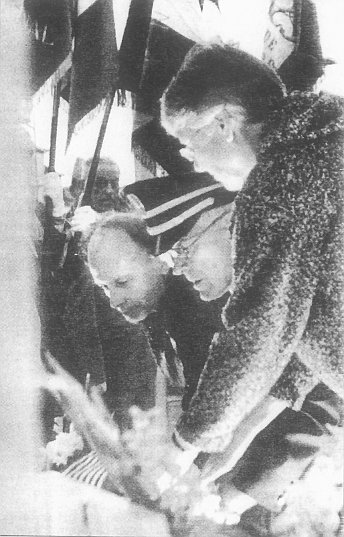

The next day dawned bright and clear. From the bus terminal near the center of Epinal, we took the No. 5 bus out to Dinoze, where we disembarked at the last stop beside a two-lane highway out in the country. From there it was a half-mile hike farther up the road to the entrance to the cemetery. Mr. Roland Prieur, the superintendent, greeted us immediately as we entered the parlor of the visitor’s building. After explaining who we were and signing the guest book, he led us out to the graves. Along the way he cut a pair of red roses from a garden and got a small pail of earth. At the graves of Irving B. Patten, my uncle, and George K. Patten, my father, he stuck a rose into the ground in front of the marble stone and rubbed earth into the inscription to make the engraving stand out. He took a Polaroid picture of each grave, then left us to visit while he returned to the visitor’s building to prepare a folder of information for us.

It was a bright sunny day and a beautiful setting. We must have spent a couple of hours taking it all in, wandering around and taking pictures. It’s good the we took the bus out and not a taxi, as we felt completely unhurried. Upon returning to the visitor’s building, Mr. Prieur presented us with a thick folio of information. He had looked up the addresses of the veteran associations for the 99th and 491st bomb groups on the Internet, and that was included, along with the mounted Polaroid pictures he had just taken.

It just so happened that we had come out to the cemetery on September 24, the anniversary of the Allied liberation of Epinal. Mr. Prieur explained that the local people took this very seriously, and had wreath laying ceremonies in the evening at all the war memorials in town, starting with the American cemetery. He invited us to come out that evening to participate, and we gladly accepted. He assured us that he would drive us back to town afterwards, as the ceremony would run past the close of bus service for the day. Then he took us in his Renault Kangoo back to the bus stop. The bus was just leaving, so he raced ahead to the next stop, and we caught the bus there.

Back in town we ate and then rested back at the Hotel Kyriad. Around 5 pm, we went across the street and took the bus back out to the cemetery.

I was expecting to stand off to one side and watch the ceremony, but Mr. Prieur had us stand in the front row on the bottom step in front of the memorial. There were speeches, then each veterans’ group placed a wreath on one of the seven stands out in front. At the conclusion Mr. Prieur led me out in front of the throng and introduced me. All I could think of to say was, “I’m very pleased to be here.” After most of the people had departed for the next ceremony, Mr. Prieur beckoned us to his car, and we proceeded down to the suburbs of Epinal where there was a monument at the firing wall where the Germans had executed 336 resistance fighters. As one man read the names of 48 of the resistance fighters, another answered, “Mort por la France.” Then three groups of three people placed a wreath on the monument, followed by a line of school children with bouquets. I was invited to stand between two men of the Savoir Francais group, and carry one of the wreathes forward with them. Afterward the mayor invited us to the wine reception at the conclusion of all the ceremonies.

But we weren’t done, yet. We got back into Mr. Prieur’s car and proceeded to the monument to the fallen French soldiers of World Wars I & II at the Place de la Prefecture near the center of town. We were introduced to the chief bishop, the chief rabbi and a professor of Greek and Latin. A band played the Star Spangled Banner and Le Marseilles, followed by the placing of wreathes on the monument. Mr. Prieur had Cheryl and I join him in placing the wreath on behalf of the Americans. The professor held our bags during this. Another long line of school children filed past and placed bouquets. At the conclusion there was a receiving line, of which we were a part, then we all walked through the adjoining park to a huge indoor pavilion for the wine reception. Mr. Prieur had me stand next to the deputy mayor while he read his speech. When he finished, the deputy mayor signed his notes and gave them to me. The wine that followed was very good. There was much toasting and shaking hands with individuals. An old gentleman recalled the only English he knew, and said “Kiss me, darling” to my wife, so she kissed him on both on the cheeks. I toasted all my wine away, and a woman brought me more. Eventually people started drifting away, and we did too, by foot back to the hotel. It had been an emotionally exhausting day.

The next morning as we were checking out of our hotel, we asked the desk clerk if the previous day’s ceremonies were in the local newspaper. He kindly tore out the article from two different newspapers and gave them to us. These are treasured additions to our souvenirs.